Establishing a Palestinian state today, in the aftermath of October 7, is not only not in Israel’s interest but is, far beyond that, certifiably insane.

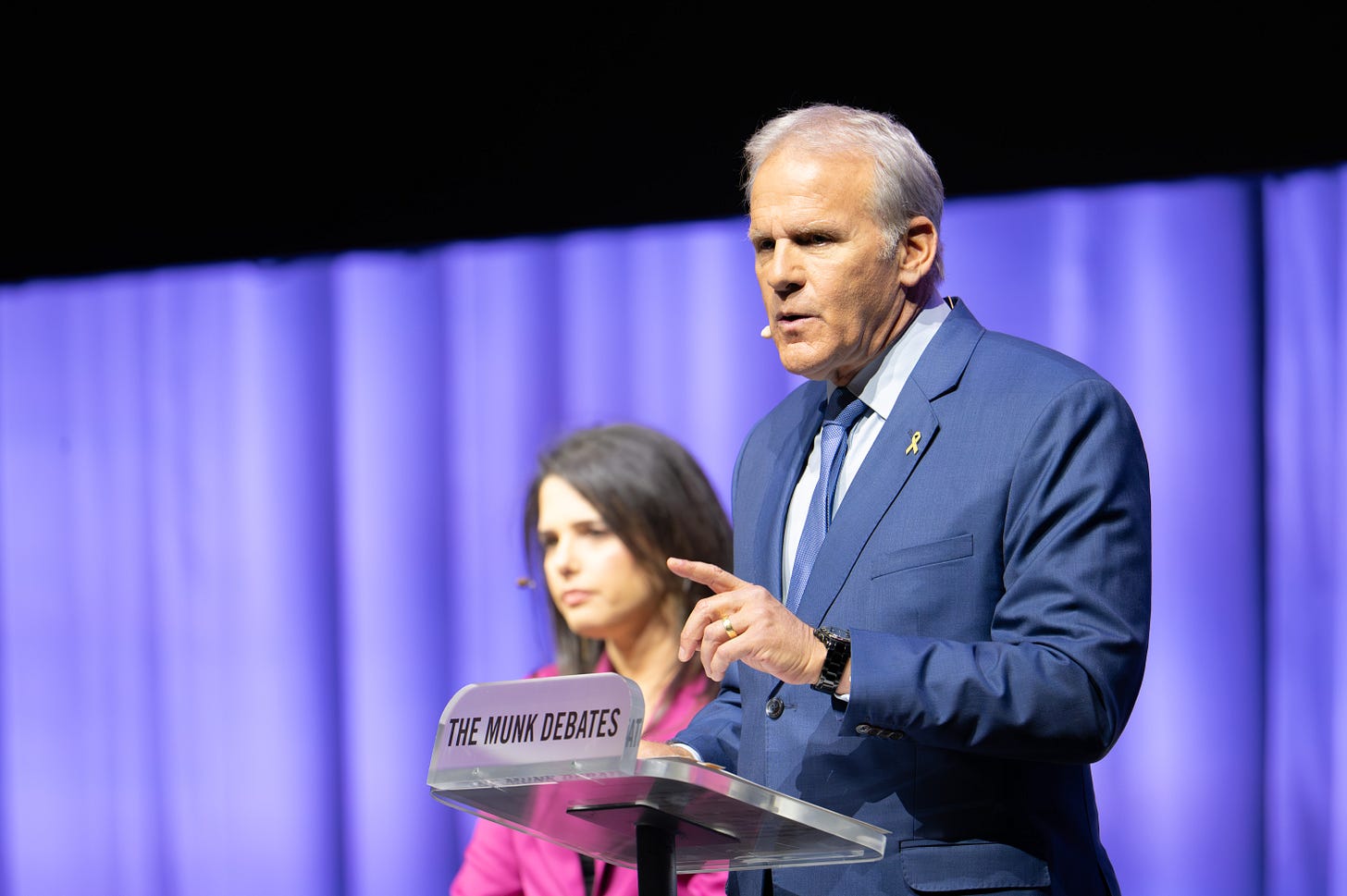

Last Wednesday evening, December 3, in Toronto, I took part in a Munk Debate. For those unfamiliar with the institution, Munk defines its mission as “to help the world rediscover civil and substantive public debates by convening the brightest thinkers of our time to weigh in on the big issues of the day.” Previous debates have pitted pro-Israel spokespeople such as Douglas Murray and Natasha Hausdorff against Palestinian advocate Mehdi Hasan and anti-Zionist Israeli Gideon Levy debating whether anti-Zionism is antisemitic. The events are always well-attended—the hall that hosted us seats 4,000—and the level of discourse is usually high. In the land of hockey, Munk supplies a riveting face-off.

But this debate would be different from all its predecessors. In this, two Israelis confronted two other Israelis in debating whether the Jewish State should support the creation of a Palestinian state.

Arguing that the two-state solution was very much in Israel’s interest were former Prime Minister Ehud Olmert and former Foreign Minister Tzipi Livni. Arguing against were ex-Justice Minister Ayelet Shaked and this writer. Addressing an overwhelming liberal audience, Ayelet and I were expected to lose, and yet we both viewed the debate as a way of explaining to the world—and especially to those standing by Israel throughout this most difficult period—why two-thirds of all Israelis now oppose the two-state solution. In fact, the overwhelming majority of even center and center-left Israelis, among them many members of my own family, feel that establishing a Palestinian state today, in the aftermath of October 7, is not only not in Israel’s interest but is, far beyond that, certifiably insane.

Much publicity surrounded the debate, virtually all of it negative. Human rights groups, arrogating a right of universal jurisdiction, demanded the arrest of Olmert and Livni for war crimes they allegedly committed while in office. Hundreds of protestors crowded the entrance to the hall, wrestled with police, and delayed the audience’s entry. Some broke past the guards screaming, “War criminals! War criminals!” But finally, if belatedly, the debate began, with Olmert presenting first, followed by Shaked, Livni, and me (you can watch my opening argument below).

We had seven minutes to make our case with three minutes for rebuttal and four for final remarks. I will not attempt to reconstruct our opponent’s arguments. Little was new. In essence, they maintained, failure to support the two-state solution will result in Israel’s isolation in the world and its moral collapse internally. Creating a Palestinian state is the only way to prevent the emergence of a binational state and preserve Israel’s identity as a Jewish, democratic state. Tellingly, Olmert stressed, “I propose a Palestinian state, I propose it not because of them…But first and foremost, I propose it because this is what is good for Israel.” Livni offered no significant additions to this line. Listening to such reasoning, Ayelet and I experienced a deep sense of déjà vu, as if we were not in Toronto in 2025 but in Jerusalem circa 1993.

I won’t attempt to summarize our counter-arguments. Ayelet, a veteran of Israel’s responsible right wing, spoke about our connection and claim to Judea and Samaria and the disastrous results of our attempts to advance Palestinian sovereignty there and in Gaza. I advanced three points: the Palestinians hold the world record, going back to 1937, for rejecting offers of a two-state solution, they’ve shown zero ability to sustain a nation state and, even if they could, would use it for launching the next October 7. Our remarks were peppered with personal stories of the family members and friends we’ve lost to Palestinian terror as well as the recent Palestinian polls showing that the majority of Palestinians still support Hamas and October 7. A decisive seventy percent of Palestinians oppose the two-state solution. About the same portion of Israeli society is against creating a Palestinian state, though for different reasons. The Palestinians are unwilling to pay the price of statehood which is acceptance of a Jewish state in any borders. The Israelis simply want to live.

I urged the audience, “Stand with the vast majority of Israelis who are telling you, ‘We want peace, but we want to live.’” History has demonstrated, again and again, that every attempt at Palestinian statehood has meant death for thousands of Jews.

Rather than providing a précis of what I said in the debate, my purpose here is to share my regret about what I didn’t have time to say—what I would have given an additional three minutes.

Firstly, I would’ve stressed that every time the people of Israel saw a real opportunity for peace—with Egypt, certainly, and with Jordan and the Abraham Accord countries—we were willing to make major sacrifices. The fact that we are unwilling to take risks for peace today is prima facie evidence that no such opportunity exists. There is currently no Palestinian Anwar Sadat or King Hussein of Jordan, no popular support for peace such as that we encounter in the UAE, Morocco, and Bahrain. But, on the contrary, not a single Palestinian leader has ever recognized the existence of the Jewish people, much less our right to self-determination in our ancient homeland. No Palestinian leader has ever agreed to give up the so-called right of return of millions of Palestinian refugees and their descendants to Israel. No Palestinian leader has ever said that his signature on a two-state solution would mean the end of all future Palestinian claims—that the creation of a Palestinian state would not be merely a stepping stone to a one-state solution eliminating Israel.

More crucially than those points, though, was the one I would direct at Olmert and Livni. Their entire arguments were centered on Israel and what they think is good for Israel. The Palestinians were rarely mentioned and, when they were, their role was as silent props for an Israeli morality play. Quite simply, in Olmert and Livni’s world, the Palestinians have no agency, no responsibility for jihadist terror, for teaching their children how to kill Jews and paying salaries to the terrorists who do. In my opponents’ universe there was no rejection of the two-state offers of 1937, 1947, 2000–2001, and 2008, no Second Intifada, no Palestinian election that brought Hamas to power. This is not merely the racism of low expectations. It is the racism of no expectations.

The outcome of the Munk Debates, curiously, is determined by an electronic vote taken before the event begins. Attendees press a button to signify “yes” in favor of the resolution or “no,” against. The winner is determined not by the absolute number of for and against votes but the number of people who changed their votes as a result of hearing the debaters. Contrary to our expectations, Ayelet and I won by a large margin. The Munk management called it “one of the most consequential main stage debates in the seventeen-year history of our series.” For us, it was enough to know simply we’d done our duty.

Later, at our victory dinner, I had the opportunity to reveal my esprit de l’escalier, a French term (remember, this was Canada) for things you wished you would have said in an argument but didn’t. I’ve recorded them all here. Use them, please, the next time you find yourself in a face-off about the two-state solution.